Lauren Bryden

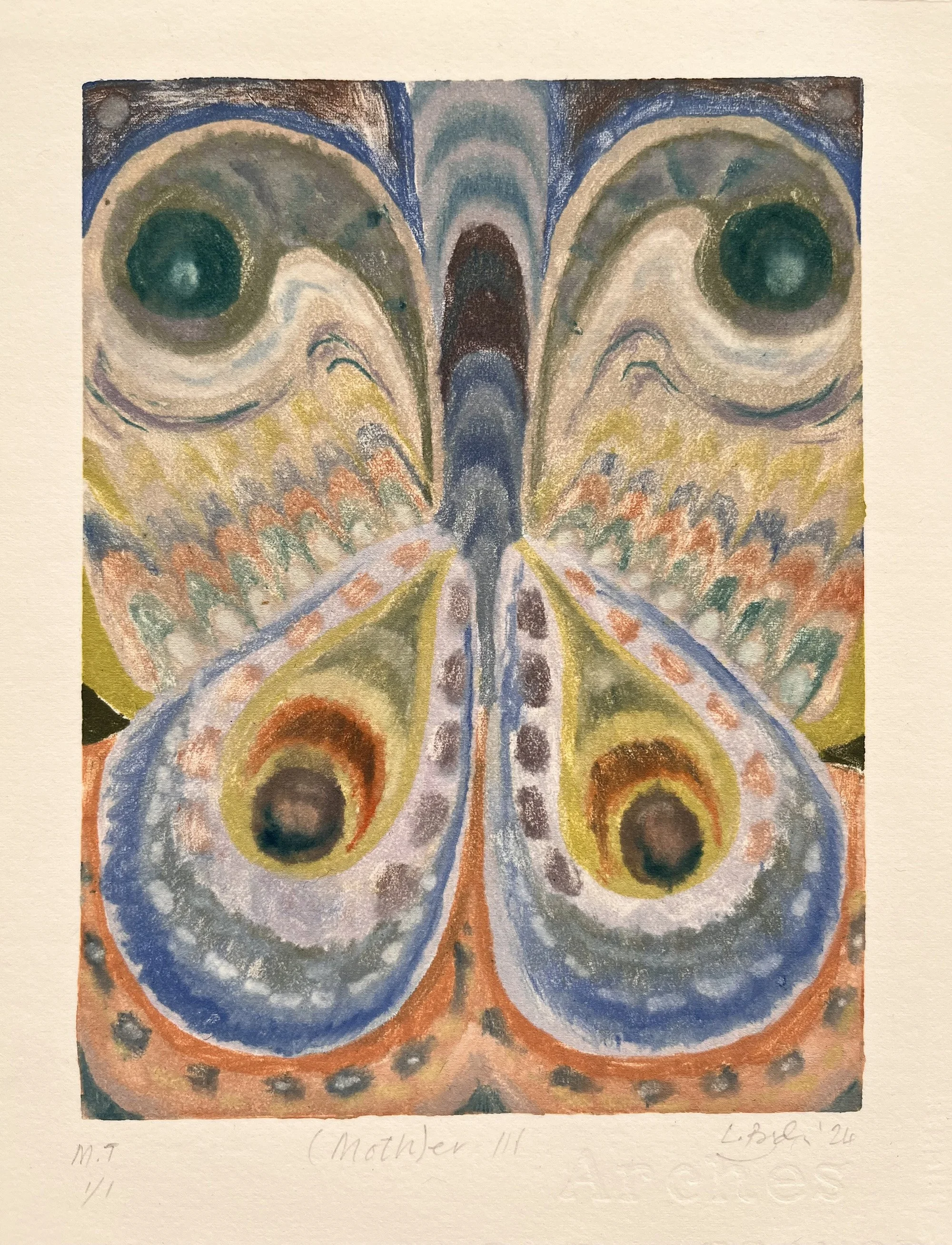

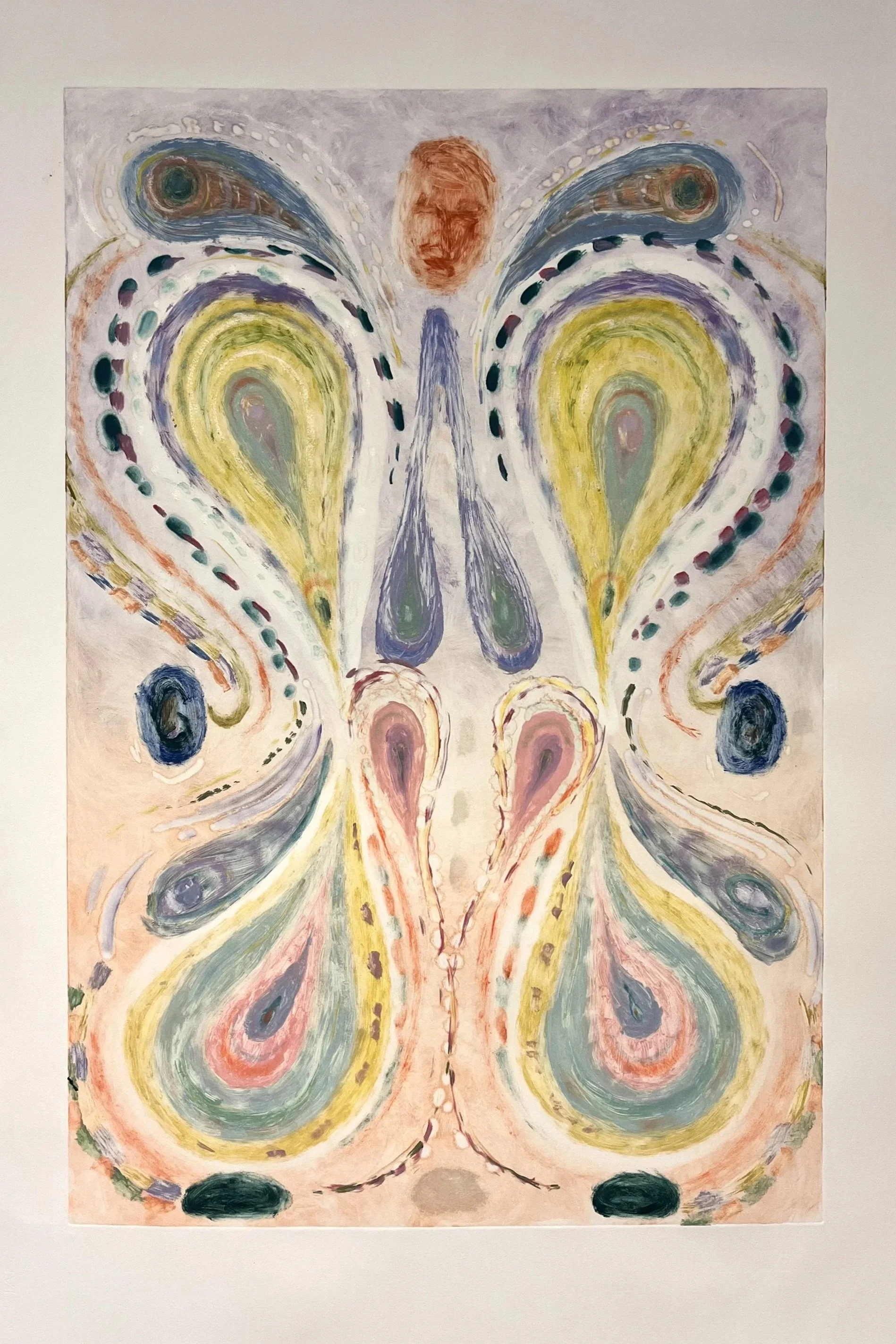

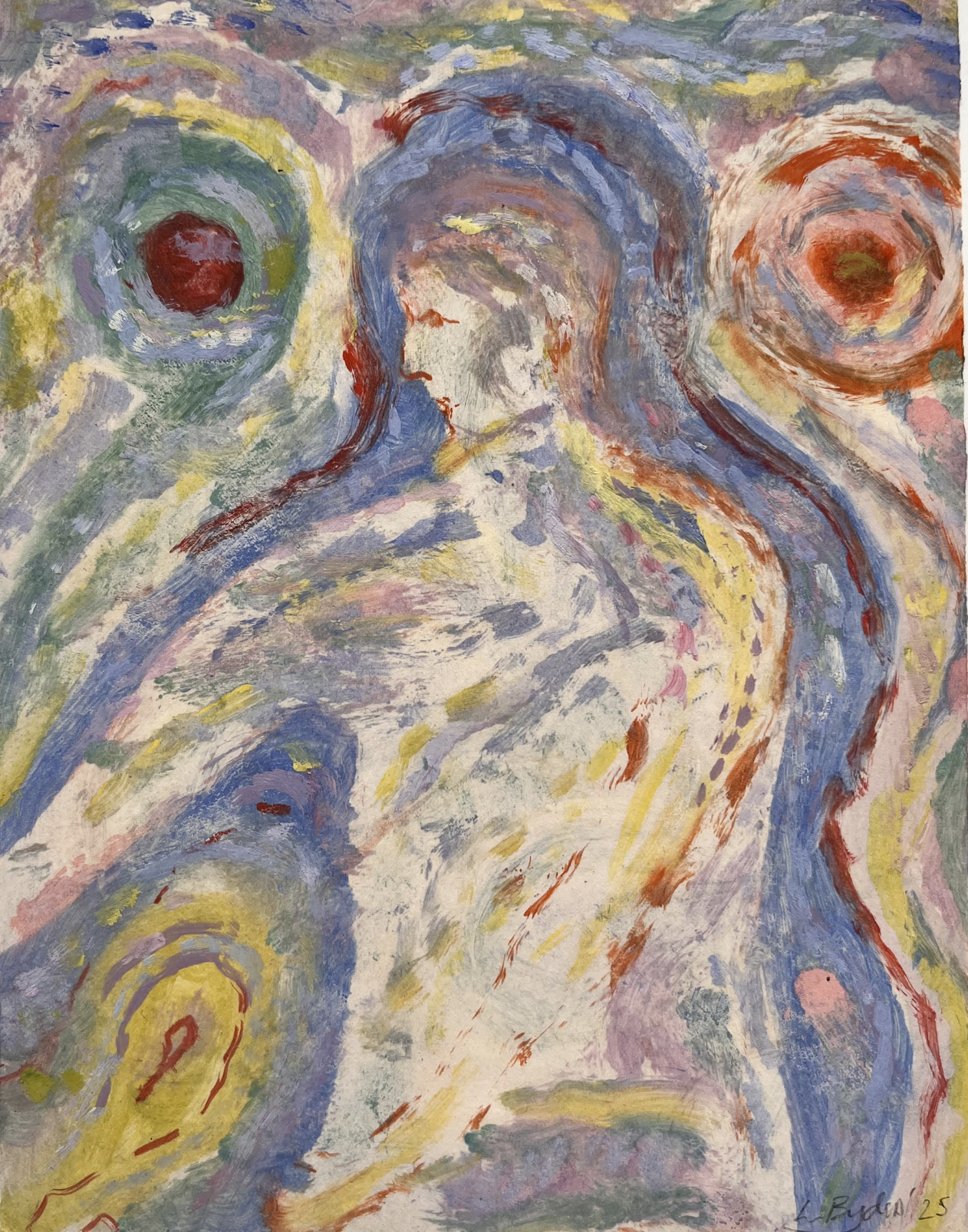

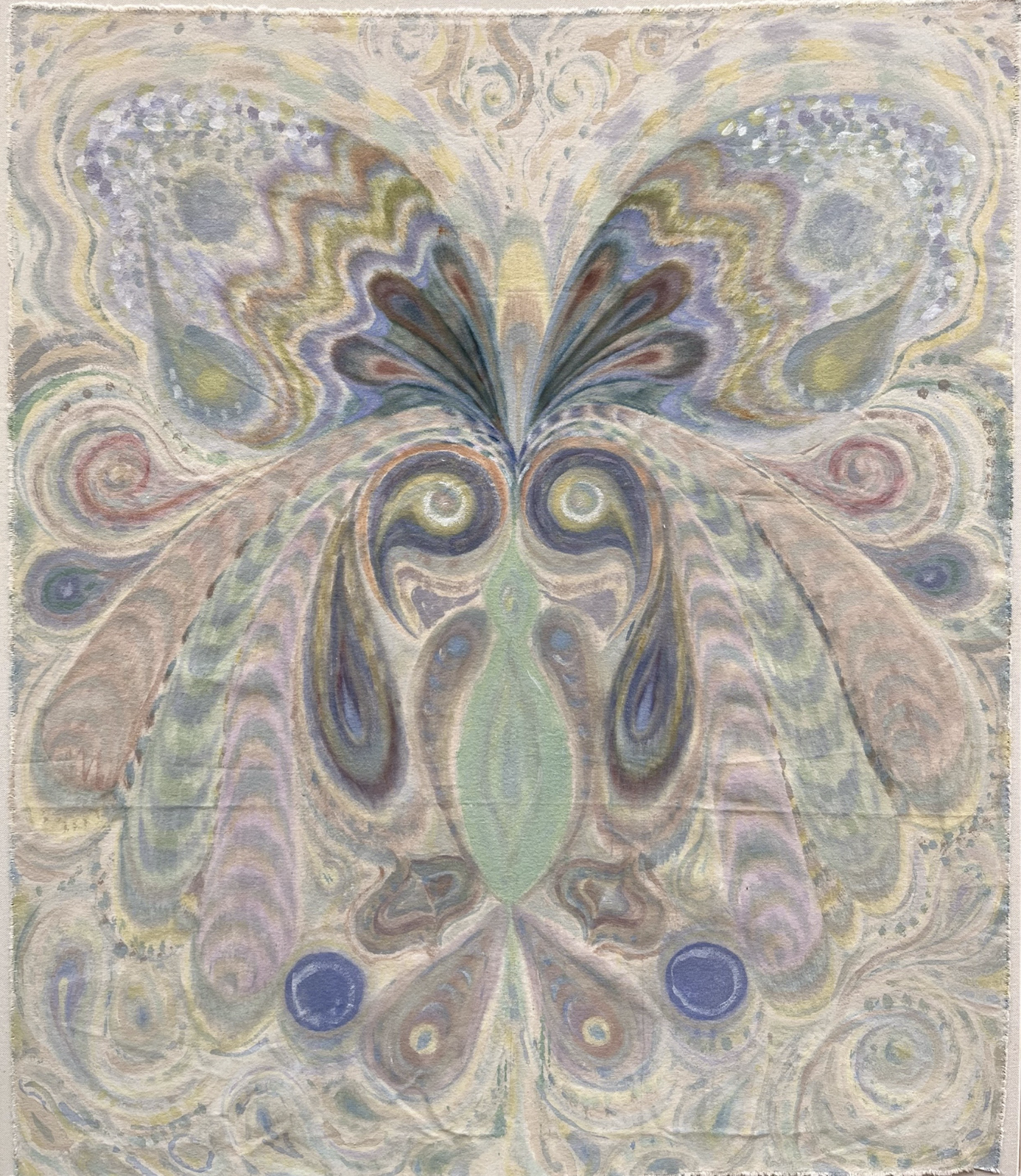

Lauren Bryden is a Glasgow-based Scottish artist known for her deeply textured, emotionally resonant paintings and prints. Her work draws us into a world where softness meets symbolism, exploring profound connections between historical plant folklore, the powerful figure of the woman healer, and contemporary experiences of transformation and motherhood. Her recent solo exhibition, “Dilation,” captivates by presenting these themes through a mesmerizing color palette and forms. We’ll be discussing how she incorporates rich history into a contemporary context, the recurring motif of the moth, and how her background in textiles informs her tactile, layered approach to painting.

Hello Lauren, how are you? Can you tell us a bit about yourself, who you are, where you’re based, and what do you do?

Hello, I’m doing well thanks! I’m Lauren, I’m an artist from Scotland and I’ve been living and working in Glasgow for the past 20 years.

About Dilation, your first solo exhibition at Paul Stolper Gallery earlier this year. What made you choose this specific word to represent the themes of the show?

I’m intrigued by medical terms for reproductive health, and ‘dilation’ or dilating is quite a loaded term, it’s often seen as virtuous and a sign of progress, and interestingly the show title prompted conversations with people and their sometimes emotional reaction to this word.

But ‘Dilation’ represents a more preternatural idea of opening up, becoming bigger, expanding and opening up into different worlds, which is an ongoing process. I also discovered it’s a term used in discussing plant biology and propagation, and it felt very fitting.

Your work draws a connection between historical plant folklore and women healers in the 16th century. How did you research this period, and how do you incorporate that history into a contemporary art context?

I love to read books about plant history and folklore, and the history of witchcraft. An absolutely brilliant book which really guided me through my research for the show was ‘Mother Tongue’ by Jenni Nuttall, where she presents the history and etymology of the words we use for carework, mothering and reproduction.

But what is important is that these aren’t ideas from the past, they’re very much in our present, and that’s what makes them relevant to me in a contemporary art context. Walking down the street you will pass weeds growing in crevices, and so many of these plants have a fascinating history in terms of their uses and their folk names, which are often regional. Plants which were once important now grow in common places and keep our connection alive to the history of healers and all that entails.

Can you elaborate on the symbolism of the moth in your work and how it relates to the idea of the "(m)other metamorphosis"?

A lot of my work utilises a ‘dyad’, an image mirrored or repeated twice in a composition. The symbolism of this presents as a dialectical relationship, for example mother and child, above and below ground, visible and invisible. The moth offers a striking and concise way of representing these ideas, and a visual opportunity for pattern making. In the moth’s mirrored wings, the dyad visually represents the unity of opposites. The motif of the moth, searching for the light, is also an icon of transformation, and is said in Scottish folklore to be a messenger between the material and spiritual worlds. I felt very drawn to this symbolism in the context of the (m)other metamorphosis.

Can you tell us more about the parallel you draw between the life cycles of plants and “matrescence”?

Personally, the evolution of becoming a parent coincided with access to outdoor space and learning to growing plants, and as I navigated parenthood I began to take solace in the similarities I found tending to plants: germinating seeds, the conditions of light vs darkness, the mundanity and the constant confrontation of life and death, beginnings and endings. There are so many canny terms in folk history and horticulture which are shared with mothering. For example, the seed potato which is planted to grow a crop from is called the ‘mother’ tuber, and in the process of producing a big yield of potatoes, she dies, and once your crop is ripe you’ll dig her up and find her mushy and shrivelled.

Making art for me is about entering a world where only me and my imagination exist, and working with and tending to plants evokes a very similar feeling.

Which other themes do you like to explore in your art?

Gender is an important element in my work, and particularly how figures are represented in my work. I like to keep the figures partly obscured or concealed, and I try not to betray a particular gender through clothing, body shape etc. Stepping into a tradition like figurative art thousands of years on, I see it as my responsibility to not reproduce expected ideas of women and mothers in art, and to broaden ideas on this in my own small way.

Your work uses a variety of media, including monotype, oil on canvas, and mixed media. How do you decide which medium is best for a particular piece, and how does your choice of material influence the final expression of the work?

In my practice my painting and printmaking both influence each other, the act of painting will give me an idea for a quality to try and achieve in print and vice versa. It’s this really enjoyable cycle which is always progressing and evolving, the two rely on each other and don’t exist separately. The monotypes I make are essentially ‘printed paintings’, there is only one print which can be made, and it is a wonderful exercise in opening up expressive mark making and being decisive. Unlike painting, it has to be finished in some way on the same day.

Your work features a soft, almost blurred quality, with a distinct use of color. Could you discuss how you use color and texture to evoke a sense of softness and emotional depth in your pieces?

I like to work instinctively with colour, rather than drawing inspiration from life. There are colours which I return to over and over which provide a sort of comfort in making art. I like to work in soft layers in paintings and prints and build these up over time; I work to the point where each piece is almost overwhelmed by colour and texture and pattern. I think this contributes to an overall sense of movement and energy and emotional depth.

You studied Textile Design at the Glasgow School of Art and Jewellery Design & Manufacture at the City of Glasgow College. How has your background in textiles and jewelry shaped your current multidisciplinary practice in painting and printmaking?

I think being able to immerse yourself in different art forms and learn new processes is a wonderful thing, and so having a sensibility for a variety of materials and processes lends itself to whatever you will do next. Studying printed textiles instilled in me a love of pattern, colour and the weight and feel of cloth. I developed an appreciation for the tactile element of printed textiles, and that it should feel inviting to touch/wear/sit on. I think I have internalised this learning when it comes to painting, and I want my work on cloth to feel tactile and soft, so I work carefully with layers and viscosity and sometimes use dyes on canvas to ‘underpaint’ it.

How do you prepare for a show like 'Dilation,' and what part of the process, from concept to completion, do you find most rewarding?

The opportunity to present ‘Dilation’ came at a point when the body of work was already underway, so it naturally came together around this theme as I progressed through the process. I think the most rewarding part of a process like this though is the ‘tipping point’ where ideas and experiments begin to come together. It goes from a state of sort of disordered chaos to a place where it all starts to make sense. It’s a terrifying moment when making art, you feel it might never work, but usually through persistence and observation the new work finally emerges and blooms.

Are there any new themes, techniques, or projects you are excited to explore in the near future?

Funnily enough, my son is really into mineral and fossil hunting at the moment, so we spend most weekends at the beach or on walks looking for treasure and reading up about our finds. It’s been a really unexpected source of inspiration, thinking about the Scottish minerals in our collection and their relationship to pigment and paints, and the bizarre and wonderful forms in the fossils we’ve found which are millions of years old, I do wonder if these forms will start to creep into the work…

Lauren Bryden @lauren__bryden

www.paulstolper.com @paulstolpergallery